I needed a ritual. More than a hug goodbye in the dorm vestibule. Better than a sob as we drove away.

The girls had chosen hundred year old Illinois schools: Nora, the enormous state flagship where her maternal grandmother matriculated; Mia, a tiny private liberal arts school in a tiny town near the Iowa border.

Mia's return to college has the feeling of another small and hard won victory. She made lemonade out of her unplanned gap year by serving as the assistant director at a local youth and special needs adult service program in Glencoe.

And now they were going away, Nora in mid August, Mia a month later. An empty nest, all at once, and I needed a commemoration, a cultural practice to guide me in and through the moment. I'll always be their mother, but from now on I would be a long distance mom, phoning it in so to speak, sending my love instead of spending and spreading it in the home we shared.

Where does my help come from? I lift my eyes to women who have kept my feet steady on the path. Sharon Olds has a poem about the return of her older children, all asleep in a hotel suite, and dear Sinead O'Conner also gives me mother wisdom in her lyric "Three Babies."

I'd been humming Sinead's propulsive dirge for days, ever since she left us, too soon, too soon. I kept her songs on repeat while I tackled cleaning out the garage on one of those precious long last summer days. I only knew a few of the words. The most important words, actually, "The face of you/The smell of you" and what expression could better bear the intensity of deep and instinctual and primeval Mother Love?

But there is another story in her song, buried beneath her obscuring keening --- with the phrases "I'm like a wild horse" comes the clue and the "I know they will be returned to me" falls with a devastating weight. I translate into the gut wrench of "DCFS."

But despite Sinead's pain (or perhaps because of it), she left me and all of us so so many gifts. One of them is this: With the girls leaving, I can interpret her poem for myself, set myself in her anguish and also the prevailing hope of another tearful reunion.

Mia joined me in the garage to help me sweep up the broken pots and untangling the mismatched Christmas lights. We spelled each other, taking turns tossing and sorting. I'm trying to keep as much as I can from the waste stream ("What if nothing is waste?" was the mind blowing slogan on the side of the garbage truck) while my dear girl is exercising her new found skill to let go and let goodness. I take her broken shards from a kiln failure out of the trash and sprinkle them in the gravel of the passthrough to the alley. Organics get dumped into another back corner of the garden, behind the overgrown mint and autumn clematis. And there, tucked away and undisturbed, was the dead baby rabbit. Unbloodied and whole, his eye still shiny but still. He could have been resting. I gasped and called for Mia, who like me, cooed with pathos at the pitiful sight. Flies were starting to gather on his fur so I suggested a burial. We'd recently uncovered the big metal shovel in the tool pile.

"Yes!" said Mia and told me about a Youtube video she'd seen that taught her the spot where an animal is buried may lay bare for a while: "The earth's process of grief" she called it, while later the fertilizing will kick in and nourish away.

I dug a shallow hole next to where he lay, handed the shovel over and Mia gently slid him in.

"Let's say a few words," I suggested, swept up in the play rite, and "Thank you, Rabbit, for delighting us when you played in the yard, even though you ate my hostas and the coneflowers"

Mia covered him with the loose dirt and my ceremony took care of itself. Thank you, little baby, goodbye, goodbye.

I will always be their mother, near or far, and Bernadette's continual mother of me endures, not through any supernatural intervention, but through my inheritance: the blood and bone and DNA and laugh and nose and eyes and flank and smile and love of children and their education and growth. And the sacrifices I have made and will make.

Thank you, Universe, for sending all the things as I need them. Even if I get impatient, often, waiting.

*****

Nora had also joined me in the garage the first day I stared the dusty, cobwebby task, but not voluntarily. Earlier that day I was standing alone, looking at the two kayaks resting on the dead-leaf-strewn floor and knowing from experience that by myself, I could lift the end of each one into the looped strap hanging from the rafters, then slide down to the other end and finagle it into the other loop to store it overhead. But I wasn't feeling it this time.

Nora was finishing her breakfast in the kitchen. She was leaving in a less than a week.

"I need your help."

"Let Mia do it." Mia's recycled canvases for the plein air landscape workshop she's leading tomorrow are littered across the living room floor, half gessoed and prepped.

"Mia is working for her work," I reply, frustration mounting.

"Ask Dad!" Nora insists.

"He's working." Randy glances away from his screen set up on the dining room table to give me a "Don't get me involved" look.

Nora heads upstairs and my chest tightens up.

"Nora!"

"Don't yell at me," still ascending. "I won't help you if you yell at me."

And that power move snaps my last nerve. I pound up the stairs behind her, up to her now locked bedroom door.

I call, "You have to do your share! You have responsibilities since you live here. If you say no, I'm going to say no next time you ask for the car!"

It's a petty fight. I'm tired and sad and so tired. They are leaving. When will they leave? How badly will I miss them?

Randy and I don't punish, we don't deny, and I don't really think of the car as belonging to any one of us. But I'd already lost my cool and when Nora pleads through the closed door, "Don't yell at me! I can't stand it when you yell!" I call out my parting shot. "I AM NOT YELLING. I AM TALKING LOUD ENOUGH SO YOU CAN HEAR ME THROUGH THE DOOR."

I knew I was playing the villain but she was the one not helping me. I go back to the garage, take a breath and lift one end of the blue kayak.

"Blue Bayou" is the name I've given her, inspired by a paddle that Mia and I took down the Chicago River last week. The red boat is the punny "Cinnamon Bark" and wouldn't it be pretty if we had their names painted in script on their bows?

If I hook the t-shaped plastic handle of Blue Bayou's tether strap into one of the loops hanging from the ceiling, the prow will stay suspended so I can get the point of the stern into the opposite loop. Then I can go back to the front end and lift. It takes a few tries, I can't see the loop and my grip is awkward. I've dropped the boat a couple times doing this solo.

I've got her up and secure when Nora appears in the doorway.

"Oh honey," I say, "I'm sorry..."

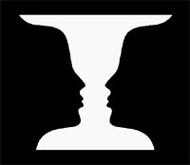

"Don't you fucking apologize," she says and bursts into tears. I'm shocked. She's taller than I am now. She goes out with her friends to restaurants and a couple of times to dance clubs and once a waiter told her and two of her friends that the family next to them (well, actually, the dad of the family) had bought them dinner. It's like that old chestnut image I had drawn on the chalkboard during summer school in June to illustrate the vocab word "ambiguous." A vase or two faces? Was the dad a creep or a caring stranger? Both? Was I a monster or did she overreact? Both? Is she a child or a teen or a college freshman or a young woman or all of the above?

"Okay, okay," I acquiesce.

I might be right but she's in real tears. And she is here, helping me. She holds up the red stern and I slip the bow into place. It's so much easier with her than without her.

"Thank you, honey" and she leaves and I worry for the next couple of days at the strength of her emotion. There's so much she has only hinted at, so much friend and boy drama. And she was leaving very soon.

*****

One more ritual.

Nora had launched, beautifully to my proud eyes. Mia had a few more days here at home, finishing up her job and her dog-sitting, packing and recycling so much of the extra t-shirts and craft supplies from her stuffed closet.

I'd offered my cousin Sally and her hubby Erik a ride home after their return from a month in Denmark. Mia loves them both and wanted to return to a weekend in Saugatuck, but the packing boxes that Nora filled so easily remained unfilled in the chaos of Mia's room.

She stayed home with Randy, I drove Sally and Erik back to Michigan, and I would be back by Monday to drive to Mia's school. Yes, yes, it was Mia's last weekend with us. And I still needed to take this road trip I had been looking forward to.

Sally and I chattered so furiously on the ride that I missed three exits. Exits I'd taken dozens of times, lol. The next day we hiked the Crow's Nest Trail along the crest of the Baldhead dune, past the Oxbow art colony, out to the overlook with the Lake Michigan spread before us. Sally's hiking group is a fast-moving, fast-talking one but I kept up and loved the conversation about the mansions on the river and their eccentric denizens.

A couple of hours later I was on the way home, but our morning hike had not been quite enough beauty of this gorgeous summer day. I dallied in farmland before hitting the highway, picked some apples, a pint of raspberries and a box full of nectarines at Crane's Upick (not to be confused with Crane's Orchards across the street, lol), then re-found a goat farm I'd taken the girls to years ago.

The farm's cheese shop resides under the trees in a tiny shack between the gravel parking lot and the goat pasture. All was quiet. Was there cheese today? Were they closed? I opened the door to the shop and found a loud crowd of shoppers vying for the French herb chevre and cow's milk "Poet's Tomme."

I laughed and said to a couple nearby, "I thought I was in the middle of nowhere!"

"So did everyone else!" and we laughed together.

The last time I was here with my little lovey girls, I asked Mia to hold the camera and I vamped in front of the wire fence in front of a sow. It's a little shtick of mine -- I've va va voomed in Mexico in front of a herd of coatis raiding a row of garbage cans. This time around, without my little giggling audience, it's not quite so fun.

An hour or so later, I was part way back to Chicagoland, but still jonesing for more soaking up of the day.

I pulled off the highway at New Buffalo and made my way to the beach. "FULL" said the parking lot sign but I turned in anyway, counting on the late afternoon nap exodus, and found a spot, no problem. More challenging was the line into the one women's bathroom so I made a fool of myself contorting into my tight striped two piece swimsuit underneath my sundress.

Crowds and crowds on the boardwalk, on the sand, in the waves. I walked on and on along the waterline, smiling at the babies and toddlers, grooving to the drifting gusts of music from clusters of lawnchairs. Found a spot almost to the edge of the public beach, where the sign says "All Long Haired Freaky People Need Not Apply PRIVATE PROPERTY." Dumped my stuff next to a group of collegey kids and entered the surf. The sensation was delicious -- the water was only a few degrees cooler than the air. But the waves, the waves, the lift of the waves, that was what I played with. Floating and sculling with those old water ballet tricks I learned at Girl Scout camp, I locked my knees straight and lifted my pointed ballet feet up out of the water, wiggled my toes and splashed forward into a somersault.

The water and me, playing. Mother Michigan lifting me up in her arms and then swinging me down. Wave crest and trough, over and over, in a dancing game.

I didn't want to leave. I didn't want to leave the water. I didn't want to leave the moment.

I tried to pull myself out, leave the weightlessness, drag my heavy body back onto the strand. No luck -- I dove back in.

"Oh!" I said, probably out loud.

Here's what I came here for -- the revelation. This in-between moment and this in-between place, is "liminal space" what they call it nowadays?

There was another moment, long (and yet not long) ago, when I didn't want to leave the water (Jesus, the connection between these two bookends makes me flush) -- The night the contractions began and I took refuge beneath the warm tap water in our big white clawfoot tub.

Randy and I were living in a bank building on California Avenue in Chicago and he slept on while I breathed through the contractions, closed my eyes and practiced the giving in, the giving up, the limpness and heaviness that carries a laboring mother through the waves of pain.

I didn't want to leave the tub, but when the pain started to overwhelm me, I had to wake Randy. He was all action, go go GO, excited and happy, ready to drive to Northwestern. I, on the other hand, only wanted to go back to the tub. I slipped into my internal work; managing the pain took everything from me. The water was my relief -- when Randy urged me to step out and dry off, the whole world became rock hard and gravity increased me ten thousand pounds.

Palmer jokes to this day about how he thought we were all ready to go, then turned around and found me back in the tub.

Finally, I gave in. I left the water, stepped into clothes he had found and walked out of our home. No checking for keys, alarm, lights, luggage, wallet, nothing. Just walked away from my old life.

And twenty years later, here I was in the water again. But this time the pain of leaving was facing a world without my girls in my daily life. Being the mother from far away instead of holding them in my arms, seeing their beautiful faces close to mine.

And yet. And yet.

Here's the secret that shhhhhh (mothers who love and sacrifice are not really supposed to feel...) DROP DEAD EXCITED. I AM THRILLED. (shhhhhhh!)

Mexican director Alfonso Cuaron's 2001 blockbuster film Y Tu Mama Tambien (And Your Mother Too), Oscar nominated for Best Original Screenplay, hides a profound mediation about friendship, love, lust, and mortality within the framework of a roadtrip sex romp: Two randy teen boys go with an older woman to the beach.

The film closes with a bang, but gives us an even more devastating penultimate scene in the moments before.

Watch, watch, watch the entire film, please. Then relish in a magically designed moment of silence broken by the percussion of water on our ear drums as Julia dives beneath the waves and emerges baptized.

The narrator tells us, "She stayed behind to begin her exploration of the local coves. The last thing she told Tenoch and Julio was: 'Life is like the surf, so give yourself away like the sea.'"